FEATURE | Time to rethink the concept of coastal defence?

When dealing with capital projects, we have seen the navies of the world modernising their capital ships and their ability to project power. While there is little doubt that that kind of sea power is becoming increasingly important in terms of protecting national interests, trade routes and alliances, there is a question that remains in the background of many discussions. Is it time to rethink the concept of coastal defence and to look at establishing capabilities to not only defend the coast but to respond to critical events along the coast?

While the geopolitical aspects of naval power are quite evident and well-defined in the public eye, what is missing is how the various coastal authorities are preparing for more difficult conditions along the coast.

If we look at the primary responsibility of a government being the protection of its people, we can see two challenges in the future. The first is the expansion and growth of major cities. The various UN studies show that there is a trend for the major cities to continue to expand in terms of population but not necessarily in terms of size. In short, the density of populations in those major centres is increasing. This will pose a general challenge for emergency preparedness and first responders as buildings reach increasingly higher and broader.

A specialised maritime presence

The second challenge involves a second population spread. While the urban population grows denser, there is an increasing desire within certain parts of the population to escape that density and the various coastline communities offer that opportunity. While these populations can cluster around the smaller communities, they also tend to be lighter on the infrastructure necessary to preserve those communities.

The challenge then becomes how to respond to events that threaten these communities. Obviously, there will be resources for the major urban centers. That is simply a question of population and when considering a ratio of people protected to services, the business cases for government are fairly simple. Those same cases, however, also form the basis for governments to potentially over-prioritize towards the city and to under-commit to the more rural areas.

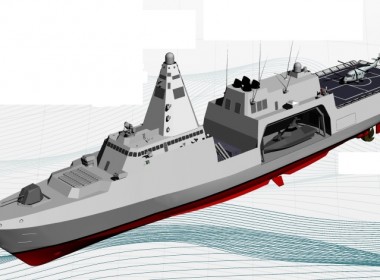

While the navy may need capital ships to project power, there is a need for the various departments that are tasked with public safety to maintain a specialised maritime presence that can be used to assist in the activities associated with preparedness, detection, response and recovery efforts. This is not the realm for a small number of capital ships but rather the realm of the small and specialised coastal patrol craft.

The reasons for this can be broken down into various assessments associated with cost, capability, and coverage.

First, we need to consider the operating environment. We need to assume that most of the man-made infrastructure is no longer in a trustworthy state. Piers may be damaged; the pilings may be eroded or destabilised. A collapsed weir may result in changes to the depth of water that precludes larger shipping from entry and it is unlikely, as we saw in events such as Katrina, that the approaches to wharfs and the like will be free of obstruction

So the first element in the mind of the government would be cost. Can one risk several hundred millions of frigate in this environment? Of course not. It would be foolish. Could one attempt to penetrate by land? Of course, but it may take significant time to open supply routes. Clearing away trees and fallen power lines are relatively simple as compared to attempting to clear and stabilise landslides or collapsed roads. And we need to be cognisant that an isolated community at the other end of that effort is on a clock of three days for water, slightly longer for sewage but also needing medical and food.

The small patrol craft for the emergency response team makes more sense in this environment. Given that the unit cost of such vessels is lower and the manning levels needed to operate them are significantly lower, then they can, theoretically, be arranged in greater numbers to cover a broader area. Also, should one be damaged, the impacts on other national priorities is likely to be significantly lower (both in terms of the ability to affect repairs but also in terms of simply replacing the craft).

Survivability in the uncertain environment

The second element of this involves response time. Most nations do not simply have a fleet of capital ships hanging around in port ready to do disaster relief. Even if there were four or five of these kinds of vessels available, the length of most coastlines means that response would likely be in terms of days and certainly not short hours.

The second element involves survivability in the uncertain environment. Small patrol craft can be designed in such a way that grounding is not the end of the operation. While specialised materials would be needed in much lower amounts, the sheer numbers in terms of forces involved are significantly less. Compartmentalisation is still possible and the draught of the craft allows it to operate in much shallower waters.

The main challenge involves being able to blend the speed needed to respond effectively with the ability to move equipment and supplies into an affected area. While there are those that have established large stockpiles of bottled water and the like, this is not the kind of material that should be moved by the responding craft.

Those can be moved by helicopter or small aircraft to distribution points. What is less movable by air, unless heavy lift aircraft are available, is the equipment necessary to produce water (such as the ROWPU) that can move the response from a condition where bottles of water need to be constantly ferried in (taking up flights) to one where the point of production can be established and maintained close to the affected area.

The small craft and littoral vessels that are useful in this context are familiar to those who have worked with technology such as pontoon bridges and the like. They are highly powered craft, highly manoeuvrable, rugged and multi-functional. Combined with the right kind of platform (such as pontoon bridges and the like), they can also become highly versatile.

So while nations tend to focus on the geopolitical, and frankly sexier, aspects of projected naval power, we need to be addressing a need in our response capability. Maritime coastal defence vessels may provide some naval presence, but it is likely time that coastal communities begin to maintain the capability to once again respond by sea and not rely upon road infrastructure. For those involved in the small craft/patrol craft capabilities of a nation, this has the potential to open up a much broader domain in terms of first response.