FEATURE | A global Arctic? Chinese aspirations in the north

On January 26, 2018, the Chinese government released a white paper announcing its first Arctic policy. Presenting China as a “near Arctic state”, the paper outlined Chinese interests in the region.

According to the document, these interests are based on China’s existing involvement in the Arctic through scientific research, resource exploration and shipping activities. The white paper also explained how the impacts of climate change on the Arctic would affect the entire world and the reasons why China should be concerned. As a responsible international actor, China argues that it should be involved in addressing these global challenges.

The white paper frequently mentions co-operation, and the Chinese government envisages increasing its involvement in Arctic governance structures as well as bilateral projects to be funded by Beijing. Recent examples include the Yamal LNG project in the Russian Arctic, an LNG pipeline in Alaska, the Kouvola-Xi’an freight train railroad connecting Finland and China, and infrastructure and mining investments in Iceland and Greenland. The paper also mentions the Chinese Communications Construction Company International Holding’s attempted acquisition of Aecon, Canada’s largest construction company.

China’s new Arctic policy is the latest addition to its Belt and Road Initiative, which Beijing touts as an economic initiative but which many see as a strategic move to acquire influence throughout the region. Steeped in historical references to the ancient Silk Road connecting China and Europe, the initiative was introduced in 2013 to connect China and Central Asian countries. The 2015 One Belt, One Road (OBOR) Initiative promises to connect Asia, Europe, the Middle East and Africa through infrastructure projects both on land (the belt) and at sea (the road).

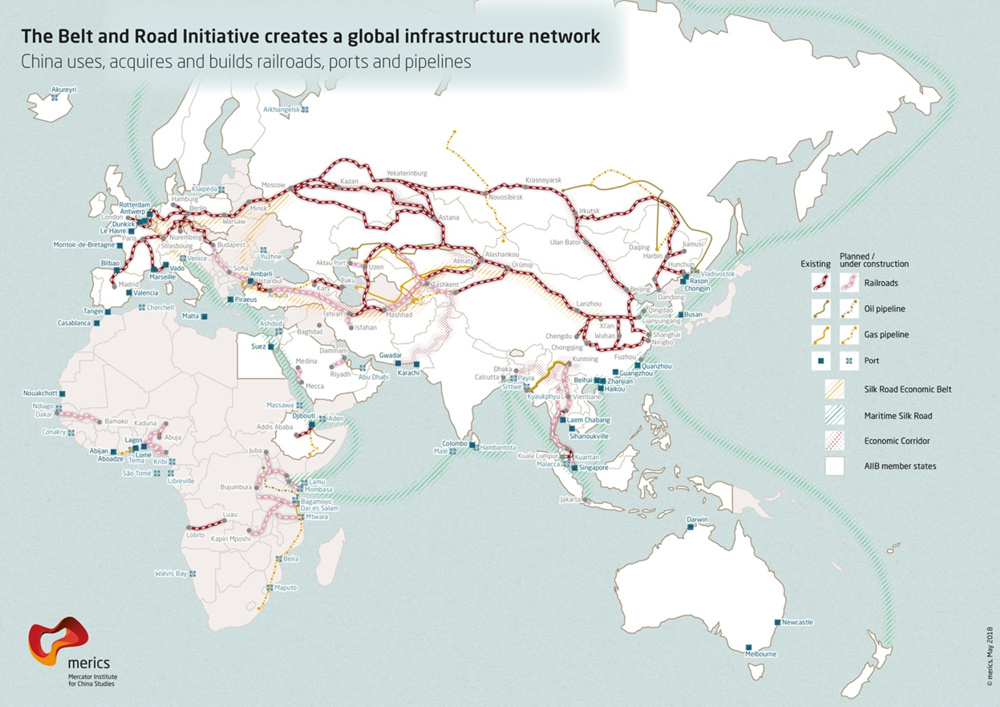

These two silk roads (the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road) are more than routes; they are infrastructural networks. To realise this ambitious network, the Chinese government plans to invest US$900 billion in infrastructure projects including railways, pipelines, ports and power plants. According to the Mercator Institute for China Studies, China had already invested more than US$25 billion by 2018.

The initiative was put on a more permanent footing through its introduction into the Chinese Communist Party’s constitution in late 2017. China experts interpret the expansion of the Belt and Road Initiative’s geographical reach to include the Arctic, as an indication of how this economic and trade initiative has become an integral part of China’s overall foreign policy.

Figure 1: A map illustrating China’s ambitions for the Belt and Road Initiative. (Source: Mercator Institute for China Studies, Berlin)

Figure 1: A map illustrating China’s ambitions for the Belt and Road Initiative. (Source: Mercator Institute for China Studies, Berlin)

China’s new Arctic policy adds a polar Silk Road to the grand scheme. Chinese media also like to refer to this northernmost addition to the Belt and Road Initiative as the “Silk Road on Ice”. This vision has led many observers to warn of China’s attempt to get a stronger foothold in the Arctic. However, it is rather the policy manifestation of existing Chinese activities in the Arctic.

Already in 2013, Beijing became an observer to the Arctic Council. In 2014, President Xi Jinping announced in a speech that China wanted to become a “polar great power”. For years now, Chinese companies have invested in numerous infrastructure, mining and drilling projects in the Arctic. In the summer of 2017 Beijing tested the commercial viability of the Northern Sea Route along the Russian coast and the Northwest Passage.

The Chinese research icebreaker Xue Long (Snow Dragon) traversed through Canadian and European Arctic waters supporting scientific research but also collecting knowledge that will be useful for future cargo shipments. The state-owned China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO) is already shipping goods through the Russian Arctic to European consumers.

For Canada, the significance of the polar Silk Road initiative does not lie so much in the potential threat of Chinese commercial shipping through the Northwest Passage nor the purchase of Canadian Arctic ports. Experts agree that the Northern Sea Route along the Russian coast with existing port facilities and the geographical proximity between Russia and China will always make that route a more attractive one for China.

It should also be mentioned that, even though China’s Arctic investment nowhere near matches the billions that Beijing spends in Africa or Latin America, no other outside player is investing so much money in the Arctic, as the region is characterised by high costs and slow payoffs.

There are a number of northern communities that welcome any capital, especially independence-minded political actors such as the Partii Naleraq in Greenland, which would prefer such investment over money from Denmark. Of course, the Canadian government should be vigilant about any future Chinese large-scale infrastructure investment in the North, not least because the United States may be actively opposed to such activities within its continental security perimeter.

In terms of foreign policy, it will be more important for Canada to interpret China’s Arctic policy as yet another articulation of interest in Arctic matters by a global player. The EU did so much earlier using similar language. A closer reading of the white paper reveals these similarities.

The Chinese argued in 2018 that, “the Arctic is gaining global significance,” and that changes in the region have, “a vital bearing on the interests of states outside the region and the interests of the international community as a whole, as well as on the survival, the development, and the shared future for mankind”.

This echoes the arguments that the European Union put forward in its policy documents in 2008: “In view of the role of climate change as a ‘threats multiplier’, the Commission and the High Representative for the Common Foreign and Security Policy have pointed out that environmental changes are altering the geo-strategic dynamics of the Arctic with potential consequences for international stability and European security interests calling for the development of an EU Arctic policy.”

In both cases, increasing accessibility of energy and mineral resources, as well as climate change, have been used as justifications for conceptualising the Arctic as a region that has attained global political meaning beyond its limited geographical space. Ottawa will have to accept that any state which sees itself as playing a role in international politics will want to be somehow involved in Arctic matters. This is not dissimilar from China becoming a contracting party to the Svalbard (1925) or Antarctic Treaty (1983). The Arctic’s global significance over the past 10 years means Canada must avoid other conflicts spilling over into the Arctic. So far, tensions between the United States or Canada and Russia over the annexation of Crimea have not substantially affected co-operation in the Arctic Council.

Usually, Canada’s foreign policy within the hemisphere is very much influenced by its relations to its neighbour to the south. Due to the current US administration’s latent disinterest in Arctic matters – especially since the shale revolution diminished the lure of oil and gas resources in the Arctic – international governance and politics in the Arctic will be driven by discussions of global challenges including energy security and climate change and facilitating the entry of non-Arctic states into these debates. This development will only intensify as climate change further impacts the Arctic region.

Article reprinted with permission from the Canadian Global Affairs Institute.