What is “artificial” and what is “intelligence”?

Today, there is so much excitement and claims and the feeling of empowerment made by many using artificial intelligence (AI). Is it a tool, is it providing solutions, is it exploring avenues untrodden, or is it just hype created by those that have created the algorithms that anyone can become an expert, to line their own pockets? Are those using it lying about their own ability in the solutions they have offered or “created”?

So, what do we mean by AI? The term artificial, by its very definition, suggests that nothing is real, merely a simulation, if you will. It is a means of simulating intelligence, by using a machine, in this case a computer.

What, then, is intelligence? This is the realm of knowing and reasoning and understanding. Thus, the process of learning and understanding requires a vast database of information to acquire some degree of pattern recognition and the “ability” to make informed decisions based upon them, to provide an output that simulates creativity and autonomy.

When asked about AI, it is fair to say that most people would not know about the Turin test. This test examines if a machine (in this case the computer), when answering a series of questions, could pass off its responses as being those from a human, not a machine.

That was the basis of the definition of AI in the 1950s. This was later superseded by machine learning in the 1980s, wherein AI systems learned from historical data. This then brings us to the next generation, that of deep learning, in the 2010s, wherein machine learning models would mimic (as best they could) the human brain.

This leads us to where we are today (in the 2025+). We now have generative AI (GAI), which uses the previous deep learning models that created original content. It is this “original” content that has many either in awe and wonder or citing copyright and IP issues being disregarded, not to mention the current inappropriate output by some GAI models, owing to a lack of regard for adherence to any form of regulation.

Can (or rather should) naval architecture follow the route of using GAI, or AI for short, in design?

If we look at the front end of naval architecture, the presentation side, there are many image creation tools such as Vizcom. They state, “Go from sketch to photorealistic 3D render in seconds.”

The ability to save a huge amount of time in turning a sketch, or an idea, or an outline of a design into a professionally finished image that would otherwise take days or even weeks does indeed sound like what one would expect from a great tool. Saving time is always one of the many objectives of a naval architect, as production waits for no one.

So, in this instance, if one is able to produce the same output manually, yet within a vastly greater time frame, why would anyone not wish to use it? We all use power drills rather than manual drills for the same job, don’t we?

If, on the other hand, one is lacking in such skills and knowledge to perform the image creation task manually, isn’t this also great news?

Well, not really – not from a professional standpoint, at least, since having an idea or a sketch of “something” does not equate to having the skills, intelligence and knowledge to be able to convert the idea into reality.

I could simply draw a large red button and under the button have the word “engage”. I can claim pushing that button will have me instantly transported to the other side of the world, my claim or idea being that it saves on flight times.

The downside is I just need to wait for someone else to invent the technology to tele-transport a human across the world, but because I drew the original idea of the transportation button that becomes synonymous with instant travel, does it make the technology behind it mine and my IPR?

It obviously does not, and yet, isn’t this what is being done with AI on someone’s simple sketch, with zero to minimal professional skills of illustration technique and understanding of form and function, to provide gravitas and a notion of “expertise”?

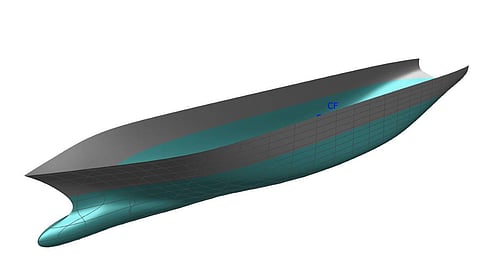

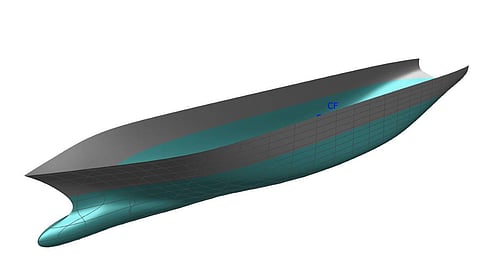

There are now some who are stating that they can create a hull form, which is efficient and optimised, within seconds using AI tools. So, where is the AI obtaining its database of information from which to identify patterns and understand what efficient and optimised means? It would be like walking down a street and seeing 100 cake shops, and all of them stating they have the best cake. Who decides which is best and why?

So, which (cake) would be selected, and what choice do you, the user, have over this automated input of pattern recognition that is going on behind the scenes? Optimise is also a very over-used word, as it has way too many different meanings, most of which are lost in translation.

The hull, (back to boats) could have been optimised to be built cheaply in a small shed, thereby creating a unique set of geometric constraints. Or it could have been optimised to allow for significant changes in the displacement, for its ability to operate with major changes in payload without running aground, and so on.

Does the AI merely search for the word “optimised” and then obtain the hull form associated with that optimisation process?

Or, more likely, what about if the hull form has been obtained from endless CFD plots and CFD data without any real-world validation or verification of the results (as discussed in December’s column)? The result would be a lot of hull forms analysed using CFD that are littered all over the internet with very little, if any, verification whether that CFD output is correct.

So, the AI designed the hull forms, but how much verification is there in the input constraints given by the user? Or is the goal merely to state the hull form is AI-generated and is optimised across literally millions of hull forms that are available on the web, just to appear knowledgeable in hydrodynamics?

In a recent white paper report by BMT on the use of AI in naval architecture, one line struck me:

“Machine learning can help in the early stages of the design by showing the impact of initial decisions such [sic] frame spacing and bulkhead positions. This capability allows designers to evaluate different structural configurations quickly, identifying the most effective solutions for strength and stability…”

Well, this may be true, but when I was still a young naval architect, this was one of my many tasks along the steep learning curve of shipyard naval architecture. And doing exactly that helped me gain an understanding of structural design as well as the do’s and don’ts.

And coupled to this are understating that class rules for structural design are merely the minimum requirements, not the gold standard, and discussing the solutions with production to establish which is cheaper to build and if it can indeed even be built.

Is this another case of jumping to the front of the queue, quickly, to look and sound intelligent by obtaining an answer that would normally take many years of hands-on, real structural design experience in a shipyard? I am reminded of the excellent sketch in Little Britain, a UK comedy show in the 2000s, where the counter assistant taps into her keyboard and keeps repeating “computer says no” following an enquiry from a customer.

And, just like the Vizcom illustrations in seconds or the drawing of the simple red button without any prerequisite knowledge of technology, is the AI tool being used to save time, or is it really a salesman tool to self-inflate one’s actual skill set that would otherwise normally take years to learn? Ten years of experience takes ten years, not ten seconds on Google or using AI.

This is not a soliloquy from a Luddite, but a warning that if one trusts too much in a process that is opaque and without any control of the means for data acquisition, the lines between professionalism and amateurism are being seriously blurred. Perhaps we professional engineers need a simple logo, or icon, noting the data being presented used AI in its generation.

At least this provides a little bit of, “forewarned is forearmed”.