Any aspiring naval architect at university would no doubt be presented with a library list of reading matter to supplement their studies: from structures, to hydrodynamics to fluids, to materials, etc, etc.

It is also highly likely that one of the best books on all things naval architecture, that any diligent student would have read, is Basic Ship Theory by Rawson and Tupper.

The following question is posed in the introduction: is naval architecture art or science? In the opening chapter the very point is made that, "art had proved to be inadequate to halt the disasters at sea or guarantee a client of their money’s worth and that science produces the correct basis for comparison of ships but the exact value of the criteria [that] determine their performances must…continue to be dictated by previous successful practice".

The most interesting point made in the same paragraph is this: "Where the scientific tool is less precise than one could wish, it must be heavily overlaid with craft; where a precise tool is developed, the craft must be discarded."

Allow me to quote an axiom that any naval architect is familiar with: "Well, it depends!"

So, a tool can be anything that enables the naval architect to design a vessel. This could be anything from a simple pencil and paper, or a set of ship curves, or a software program that can now do this in the digital environment, such as Maxsurf, or Rhino.

And this is a very good example of a precise tool being developed and previous methods being phased out, or simply discarded. Walk into any design office and all that is visible are desks with PCs and keyboards – not a drawing board in sight.

However, this precise tool still requires the “craft” or the knowledge and experience of those before in creating a fair and developable surface for plate development. The software may have additional tools within its arsenal to provide guidance, but it won’t explain the "whys."

Thus, just like any tool around the house, knowledge of what it can and can’t do is needed. One wouldn’t use a handsaw to drive a nail into the wall. Whilst this example seems obvious, today’s tools for naval architecture, owing to their increasing access of complex disciplines via a simple user interface, become a recipe for blurring the lines between not just science or art, but into a subject of salesmanship.

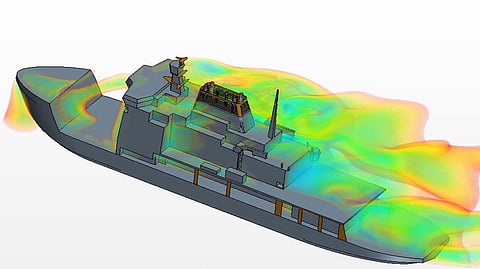

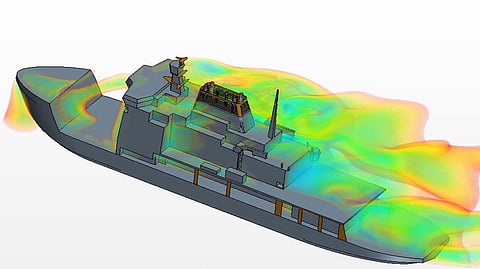

Take computational fluid dynamics (CFD) as an example. This is now a tool used by many design houses, owing to its accessibility and affordability.

With each passing year, desktop computers are becoming more and more powerful and they can now utilise these highly complex, memory-hungry programs that once seemed near impossible only one or two decades ago. With hull forms that are now created totally within the digital environment, transferring the hull into these programs is child’s play, right?

So, looking back some 14 years ago to the International Towing Tank Conference (ITTC) symposium on CFD, interesting conclusions were made and highlighted:

"For unconventional ships such as multihulls, planing boats and new-concept hulls, it is a little harder to assess the state of matters due to the difficulty of finding systematic and well-documented studies in the open literature…the prediction error for unconventional ships…with all design details would be somewhat larger than with conventional ships."

This then sounded a warning that the accuracy of using CFD is still suspect and requires further verification, validation, and correlation.

Looking at last year’s (2024) ITTC CFD committee report, has things changed?

Yes, of course. CFD has matured significantly in the last decade, and many ITTC towing tank institutions use them regularly. These institutions have access to such verification and validation from existing models and their tank test data to tweak and modify their CFD models to become more reliable.

Several questions were asked where more than 40 institutions worldwide replied. The most striking consensus was, "We need more measurements to continue to understand how to use CFD reliably in our profession."

This is illustrated very well in a detailed and comprehensive paper published in this year’s March edition of Ocean Engineering, titled, “Resistance prediction using CFD at model- and full-scale and comparison with measurements.”

They used a powerful yet commercially available software program to investigate a ship called Lucy Ashton, which is a paddle steamer. Their reason was that the vessel had a unique experiment conducted in the 1950s where jet engines were fitted on the hull as a means of propulsion, as this negated the need for propellers to be modelled and their interaction effects. Thus, a full-scale ship of hull only is an ideal means of analysis.

However, upon reading their conclusions, the words of the 2024 ITTC committee are evident in all their findings. These include the following:

The smearing of the free-surface on the surface of the hull was found to be problematic in all the simulations carried out.

The simulations at full-scale and the comparison with the measurements show the resistance coefficient to be under predicated for all Froude numbers when surface roughness is not included.

The comparison performed at model-scale also showed the resistance coefficient obtained in the simulations to be significantly lower than that from the measurements.

Using Prohaska’s method to obtain the form factor was shown to lead to large variations with the scaling ratio.

This is using one of the more high-end commercial available CFD programs, probably beyond the reach of many SMEs. Harking back to the very prophetic words by Rawson and Tupper, one could not consider this to be a ‘precise tool’, given the uncertainties and lack of verification and validation against a very simple monohull’s sea trial performance data.

And so, back to the axiom. Is CFD worth using? Is it reliable? Well, it depends!

If it is CFD used by ITTC towing tank intuitions, which use their own in-house forms of V&V from a large database of testing, then it is more likely to be correct than incorrect, or at least within the margins of statistical errors. The average SME does not have access to such a database to verify the results.

This is where the industry, or rather users of this software, must take a step back and ponder. Where the scientific tool is less precise than one could wish, it must be heavily overlaid with craft. In this instance the craft is the database of previous tank testing and/or hand calculations that were be done in the absence of this new tool. Don’t throw the baby out with the bath water!

So, this comes to the final point: salesmanship.

Given all that is known or rather not known about CFD’s limitations to the wider public, by those who are not naval architects, or perhaps even technically astute to interrogate claims, why are magazines and social media full of claims of unique hull forms or savings in resistance or improved seakeeping, yet only cite the output of the CFD as their means of validation?

Is salesmanship (in the discipline of naval architecture) the art of subverting opinion as fact, or is it more deep-rooted than that? Has the need for posts and "likes" on social media pushed naval architects from a fact-based discourse to one of pure opine?

It would appear naval architecture has come full circle, again in the wise words of Rawson and Tupper, as the art has now proven to be inadequate in the face of endless claims and postings.