A browse over the websites and publications of the various state and commonwealth bodies involved with fisheries in Australia reveals numerous claims to excellence and even assertions of "world's best" in fisheries management. Last year the managing director of the Australian Fish Management Authority (AFMA) described their management as "…actually leading the world in this stuff," and, "cutting edge." However, the statistics present a somewhat different picture.

With the third largest fishery zone in the world and the largest by far per capita, Australia has the lowest harvest rate at only three percent of the global average. The management is also the most expensive and restrictive in the world. Every year increasing management costs are delivering further decreases in production, participation and profitability while managers bask in self-awarded accolades. In a number of smaller fisheries, management costs more than the GDP of the fishery. Money could be saved by paying the fishermen not to fish and dispensing with management.

Over two-thirds of domestic seafood consumption comes from imports. All of these are from far more heavily impacted resources elsewhere. That this could be seen as unconscionable seems to have no recognition. In addition to their impacts elsewhere, these imports cost some AU$1.7 billion (US$1.2 billion) annually and the price is steeply increasing. They are paid for by selling off non-renewable resources. Calling this "sustainable management" comes close to an oxymoron.

Despite all the management, Australian fisheries are in widespread serious decline. However, in no instance does this involve a collapse of catches due to over fishing. In every case, over regulation is a major factor in making economic operation impossible. The budget for the Australian Fisheries Management Authority which manages the offshore fisheries comes to over $100,000 per vessel. State fisheries departments spend only moderately less per vessel. Western Australia has the largest state fishery. They manage a fleet of some 800 vessels for a department budget of $65 million. In both cases the biggest vessels are small by world standards and most are very small by any standard.

Largest fishing zone – smallest catch

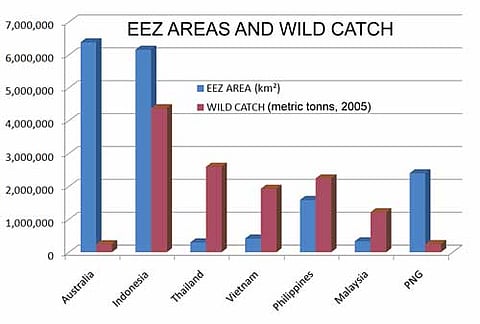

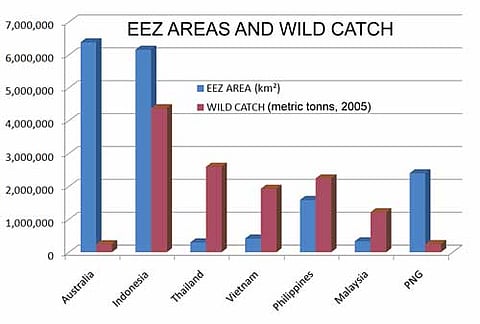

If the EEZ area and catch of Australia is compared with other nations in the region it is apparent that the fishing zone is the largest and the catch the smallest with the differences being in orders of magnitude.

(Fig. 1) Thailand, the largest source of Australian imports, produces over 10 times greater total catch with less than five percent of the EEZ area.

(Fig. 2) Growth since 1950 has been painfully slow and small. After 1990, when management really began to expand, growth ceased. In recent years both profits and participation show accelerating decline. A slight increase in low value tonnage has occurred as a result of the development of a sardine fishery to supply feed for tuna aquaculture in South Australia.

(Fig. 3) Compared to other OECD countries, total production is on a par with Finland, Germany, Poland and Portugal. It is less than half that of New Zealand.

(Fig. 4) The harvest per unit of area is almost imperceptible relative to a broad range of other nations.

(Fig. 5) Contrary to claims by our fisheries managers, neither the productivity of Australian waters nor the shelf area is small. Average primary productivity is in fact higher than that of the Philippines and even that of Japan.

Until a few years ago, low productivity was not even mentioned. It became a convenient explanation only after I brought up in public debate that claims of widespread threats from overfishing were grossly inconsistent with a harvest rate that is only three percent of the global average and less than half of one per cent of that of Thailand, our biggest supplier of imports. Suddenly an inexplicable black hole in oceanic productivity was proclaimed and the Commonwealth Minister announced that, "…Australia is in the middle of, you might say, a fish desert." Strangely, oceanographic science seems never before to have noted this remarkable phenomenon until it was needed to explain dubious claims of overfishing despite only tiny harvest rates.

Shelf area nonsense was quickly shelved

I then pointed out that global marine primary productivity measurements from satellite monitoring showed no unusually low productivity around Australia. The first response to this was a claim that the most productive fisheries are on the continental shelves and we had only a small shelf area. This really wasn't very well considered. Australia has the second largest shelf area of any nation. The shelf area nonsense was quickly shelved and the claim then became that the productivity figures were only averages and a large area of exceptionally high productivity in the north meant that most of our waters were very low. This ignored the fact that productivity everywhere varies widely with time and place and ours is not in any way unusual in this respect. It also raised a further question regarding the absence of major fisheries associated with the area of highest productivity.

If indeed our waters were so poor it would be obvious to any fisherman with experience elsewhere and would be reflected in a very low catch per unit of effort. To the contrary, above average abundance is clearly apparent. To believe the management codswallop one must accept that despite being almost non-existent compared to anywhere else, our fish somehow conspire to be caught at rates higher than where they are 30 or even 200 times more abundant. Anyone who can believe this may find a bright future in Australian fisheries management.

Fisheries management in Broome

In April 2008 I received a phone call from a fisherman in Broome. He has one of six boats engaged in a small but valuable deepwater trap fishery that was facing extinction from increasing management restrictions. As they are the only offshore fishery in the huge Kimberley region of northwest Australia and in the heart of some of our most productive waters their situation was of particular interest. I agreed to help in their struggle. What subsequently unfolded is an unequivocal example of the profound disconnect of management from any relation to the reality of actual resource.

It turned out that the fishery is limited to a total of 11 licences each permitting the equivalent of 20 traps per day for an allocated number of fishing days each year. These licences are currently fished by six vessels. Catches have remained excellent over the 18 years since the fishery began and the catch per unit of effort has trended upward. However, management has continually claimed evidence of overfishing and the number of annual fishing days has been steadily reduced from unlimited in the early years to 104 days in the main fishing zone in 2008 with a further 30 percent reduction planned for 2009. At this level financial viability would be problematic and retention of crew impossible.

In reviewing the situation what I found would beggar belief were it not true. The fishing grounds involved are fished solely by the six vessels of the Northern Demersal Scalefish Fishery. These grounds comprise over 200,000 square kilometres of Australia's extensive North West Shelf. Widespread fishing has produced excellent catches throughout the area. Each of the small vessels in the fishery effectively has over 30,000 square kilometres of rich grounds all to itself. Allowing for an overly generous catching radius of 30 metres for each trap, the total annual effort of the fishery only actually fishes 00.2 percent of the 90,000 square kilometres of the B Zone where most of the fishing is conducted. At the present rate of exploitation it would take some 500 years to fish it completely just one time and over 1,000 years to fish both the A and B Zones. On top of this are two additional large inshore and offshore zones that are not being fished at all.

By fishing one time it is important to realise that this means one trap set of a few hours within a 30-metre radius or about three-quarters of an acre. In addition, video camera observations of the traps shows that a trap only catches a small portion of the fish immediately around it.

Computer "games" in Canberra

Somehow, using a concoction of estimates, assumptions and theories plugged into a computer model, the managers have come up with what they claim is evidence of overfishing. Fundamental to their claim are estimates of total biomass for the entire fishery and its principle species. These, if distributed over the area of the B Zone alone, are 30 to 100 times less than what the traps are actually catching. It seems that the utterly impossible is not even questioned if it supports a notion of over fishing. The real world evidence from a remarkably consistent, 18-year-long, standardised sampling of around a million trap sets has been ignored in favour of an estimate based on a dubious confection of compounded uncertainties. This is then employed for management by remote control as practiced by office workers a thousand miles away who in 18 years have never even seen the fishery.

When my report was scheduled to be presented to the Fisheries Department at their annual meeting with the fishermen, management insisted on receiving a copy 30 days in advance. Shortly after receiving it, the industry association was contacted by the Department with a request that my report be deferred for another four months for peer review. The fishermen knew they were facing another 30 percent reduction to 76 fishing days in 2009, to be imposed at the meeting and so insisted on consideration of my findings. The Department spokesperson then threatened cancellation of the meeting. At that point I sent an e-mail to the meeting chairman. I pointed out that my report was in fact an independent peer review of the management of the fishery and that if they did not wish to receive it from me at the meeting it would be submitted via Parliament, the media and an irate public.

Higher management intervened and the meeting took place as scheduled. At the meeting, I pointed out that the independent peer reviewed estimate they had asked for already existed. It was published in one of the world's leading marine science journals, Acta Oceanographica Taiwanica. In the 1970s and 80s a fleet of large Taiwanese pair trawlers had operated extensively in the region under license from Australia. Based on a widespread sample of over 25,000 hours of trawling using 100-metre-wide pair trawls, they estimated a sustainable annual yield of 250,000 tonnes of demersal fish for the same area. This is some 300 times more than the 800-tonne maximum yield used by current management. It is also a bit more than the total wild catch of all Australian fisheries.

Could this be possible? Actually, it comes to about a tonne per square kilometre, or 10 kilograms per hectare. This is not extreme at all and is comparable to moderately good trawling grounds elsewhere in the world. It is also consistent with estimates based on the extensive trap catches. It amounts to a small fraction of one percent of the primary productivity of the area. It is further confirmed by echo-sounder, line fishing and video evidence of abundant fish throughout the fishing grounds. The only thing not in accord is the output from computer games designed by office workers who have never seen the fishery.

The implications of this situation go well beyond just an academic dispute or the livelihood of a half-dozen fishermen in Broome. Under the International Law of the Sea Treaty on which Australian EEZ rights to the North West Shelf fisheries are based, exclusivity requires usage. Large Asian fishing companies are well aware of the rich and virtually untouched fishing grounds off northern Australia and I have personally been told by the CEO of one such company that a legal challenge before the World Court for access is being considered. Present management would make this very real possibility most difficult to defend.

Fisheries management by fantasy

The management of the Broome trap fishery repeated a hundred fold around the country is what is wrong in Australian fisheries management. It is simply a fantasy – not even credible at first glance if accorded the most rudimentary quantitative examination.

Current management emphasises protection, precaution and sustainability. But, in itself this is a no-brainer. To achieve these aims, all that is required are high levels of restriction. Good management, however, must also entail productive utilisation of resources and maximising their socio-economic value, not just locking them up to "protect" them.

Claims of excellent management are bolstered by assertions it's all based on sound science. Examination of global fisheries management literature presents a different picture. The proliferation of fisheries management here is relatively recent and little in the form of widely regarded studies or positive results has been forthcoming. There has, though, been repeated appeal to alleged scientific findings which if actually examined either do not support the claims being made or even refute them.

Mostly, this scientific charade consists of "expert" opinions, computer models, and a liberal dose of important sounding techno-waffle devoid of any clear meaning. Although terms such as sustainability, biodiversity, ecosystem-based management, ecologically sustainable development, computer models, precautionary, overfishing, threatened and endangered all do have technical definitions they have also become ill-defined colloquialised terms of emotional index. This ambiguity provides an aura of scientific sophistication along with an element of emotive appeal. This style of eco-speak, bureau-blather, and techno-gibberish sounds impressive, means little and misleads without outright lying.

Just before the recent election the new Prime Minister-to-be announced he would take a "meat axe" to the bloated bureaucracy if he won office. Our environmental management agencies, and in particular marine management, deserve to be near the top of the list for such attention. Even if our tiny catch were indeed all our waters could sustain. the ongoing trend of spending more and more on management where the resulting production and profitability become less and less is the antithesis of the fundamental purpose of management. Making bureaucratic budgets and authority subject to outcomes would yield a quantum improvement in governance. If this could be effected it really would be a "cutting edge" achievement.

In the past, maximum sustained yield was the ideal and monitoring the performance of a fishery was the primary methodology of management. Now we have a new generation of biologists schooled in theories and enthralled by sophisticated computer models based on simplistic assumptions about complex and highly variable phenomena of which we genuinely understand very little. Although such models may be of value in gaining insights about the possible dynamics of a resource their output is fraught with many uncertainties. Typically they require generous tweaking to yield results that are within the bounds of credibility and they tend to reflect more the assumptions, aims and adjustments of the modeller than anything in reality.

Commitment to the problem

On top of all this has come the rise of environmentalism and a growing attitude that primary producers are exploiters who need to be severely curtailed if not stopped altogether. No matter how sound the supporting evidence, any suggestion that an environmental problem may not be as dire as feared receives only angry rejection from environmentalists, never hopeful interest. Their commitment is to the problem, not a balanced solution and the stakeholding they so righteously claim is one assumed with no investment.

To many urbanites the environment has acquired a near sacred status. Though themselves voracious consumers they are divorced from the production that supplies their demands. Those who support them are seen as greedy exploiters and defilers of the sacred. Even more ironically, their own chosen lifestyle is one which has virtually annihilated the natural world in the environment in which they choose to live.

The reality of a constant struggle for survival in a dynamic, ever-changing world has been replaced by a romantic notion of nature in a blissful state of harmony and balance, something pure and perfect where any detectable human influence is by definition a desecration. This sacred perspective of the environment manifests itself in language where fragile and delicate have become almost mandatory adjectives in describing the natural world.

A peculiar corollary of all this has been the enshrinement of the precautionary principle as mandating that any imagined possibility of an environmental effect must be addressed with full measures to prevent it. Unfortunately this formulation makes no reference to probability, cost, or consequences of risks and it offers a ready cloak for sundry other agendas. In fact, it would even preclude itself as everything we do or don't do entails risk, including precautionary measures themselves. Amazingly, this vacuous and pernicious piece of nonsense has even been written into the enabling legislation for the Australian Fisheries Management Authority.

Management of our fisheries has become divorced from the realities of the industry, the real nature of the resource and any factual consideration of its condition and dynamics. Fishing is a demanding and uncertain, often even dangerous, business. The ability to bear added costs and restrictions is not unlimited and their imposition should only be imposed with due care.

The marine communities upon which fisheries are based are not fragile and delicate but rather robust and flexible ones that readily undergo and recover from frequent natural perturbations. There is little risk in monitoring fisheries and addressing problems if and when they become apparent, rather than trying to take elaborate pre-emptive action to avoid an endless array of imaginary possibilities. No species of marine fish or invertebrate has ever been exterminated by fishing.

In general a much more empirically based approach is needed. Management decisions should be based on what is actually happening in a fishery, not theories and models. In view of our ignorance and the complexity of the matters involved, it would also be prudent to test measures before applying them on a broad scale and to carefully assess their results when implemented. Restrictions should be imposed only where a demonstrated need exists and results should be monitored. Much stronger involvement of the industry in formulating management measures is essential to ensure that the form of demands is appropriate to the practical realities of the fishery. Remote control management by theory without broad and ongoing assessment of actual conditions and results is a recipe only for continuing decline.

On top of growing demands and restrictions, large areas where fishing is totally prohibited are rapidly increasing. Australia now has about one-third of the total Marine Protected Area in the world. When planned additions are completed it will have near half and if the proposed Coral Sea area is implemented it will be closer to two-thirds. This is insanely excessive, especially when this is probably the only nation where no problem exists in the first place.

Government left hand has no idea what its right hand is doing

At the same time as government has been diligently closing down our fisheries it has been budgeting many millions of dollars to encourage higher consumption of seafood for its health benefits. Over the past few years a number of large scale studies published in leading medical journals have reported a variety of important health benefits associated with seafood. It is high in proteins and low in fats, cholesterol, and sodium. It is an excellent source of minerals and vitamins. It is easier to digest than red meats and poultry and is among the most nutritionally balanced of foods. It aids weight control and is valuable in reducing heart disease.

In particular, seafood is high in essential omega-3 fatty acids which are deficient in most terrestrial foods. Their consumption has been found to be of value in preventing or alleviating asthma, arthritis, osteoporosis, diabetes, multiple sclerosis, hypertension, migraine headaches, certain cancers, age related maculopathy and some kidney diseases. Perhaps most important of all, they play a vital role in neurological development and functioning. A diet rich in seafood facilitates brain development and has indicated significant cognitive and behavioural benefits for children. It has also been found to be highly beneficial in reducing depression, aggression and schizophrenia in adults as well as enhancing cognitive functioning with ageing. The bottom line is that high levels of seafood consumption correlate directly with happier, healthier, longer lives. It could also be expected to provide the additional benefit of a significant reduction in the massive cost of health care.

Ecology is above all holistic. Every organism must have effects in order to exist. We are no exception. Aiming to maximise our beneficial effects and minimise our detrimental ones requires trade-offs and balances whereby we seek to spread our impacts across our whole resource base within the bounds of sustainability. Every resource we lock up puts more pressure on others and makes balance more difficult. An unnecessary restriction in one place becomes an increased impact somewhere else.

We now face a global financial crisis, a looming energy supply crunch and emerging food supply problems. Continuing to add further ill-founded restrictions on our producers is tantamount to treason in a time of war. It is time that positive results be demanded from management, not just waffle. It is also time that real evidence be demanded of researchers, not just unsupported opinions by a chorus of "experts" singing for their supper. Above all, it is past time for the public to realise that we are all paying the price of resource mismanagement in our health, in the cost of living and in the general well being of the nation. The lumbering beast of government will only awaken when an angry electorate begins to loudly shout, "Enough is enough!"

A management review of the Broome fishery has now been scheduled. Whether it will result in a genuine re-evaluation and new direction or become just a whitewash to cover over the most obvious rot remains to be seen. Much will depend upon whatever public attention and political will might be brought to bear.

The idea that these few small boats limited to 220 traps in total and 160 days of fishing per year could be overfishing some 200,000 square kilometres of fishing grounds as is being claimed is something only the most quantitatively challenged might believe.