OPINION: Macroeconomics: Labour market tightens but inflation remains subdued around the globe

BIMCO reported in our previous macroeconomics report in April 2017 that monthly indicators were showing a strengthening in the global economy. The firm growth dynamics in advanced economies have now, four months later, had a cascade effect on some emerging markets and developing economies (EMDE). This solid growth has sparked an appetite for EMDE assets and indicates that the market expects a pickup.

In conclusion, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) expects global GDP growth of 3.5 per cent in 2017, adjusting EMDE up by 0.1 to 4.6 per cent and keeping advanced economies at 2.0 per cent as lower expectations for the US economy (down by -0.2 to 2.1 per cent) are balanced by stronger performance in the Euro area (up by +0.2 to 1.9 per cent) and Japan (up by +0.1 to 1.3 per cent).

Investors’ appetite for risk has also returned, demonstrated by low volatility in the financial markets despite geo-political risk and policy uncertainty.

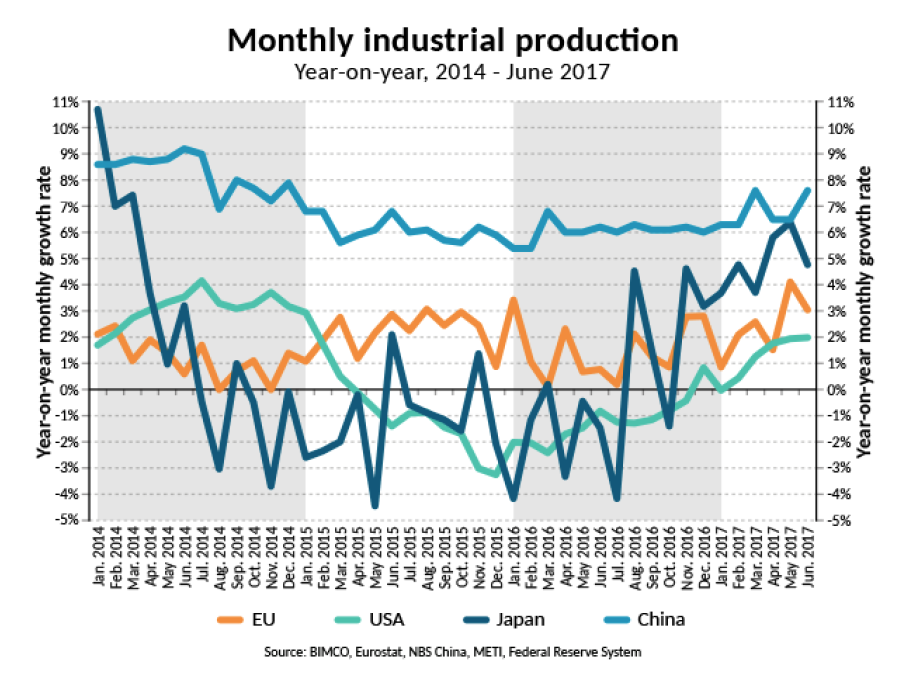

One of the global indicators pointing upwards in April was industrial production, which has increased for the four largest economic areas since January 2017. The indicator has continued to show strength throughout first half of 2017 and is a clear sign of positive development in the industries affecting global shipping the most. This is mirrored by a pick-up in global trade.

The GDP growth rate forecasts for Europe and Japan have been upgraded in the most recent outlook by both the IMF and the World Bank. It comes on the back of stronger domestic demand and higher export figures, coinciding with growing industrial production. In May 2017, the European Union (EU) experienced year-on-year industrial production growth of 4.1 per cent, the highest growth rate in more than six years.

Japanese industrial production has rebounded from a bad and volatile period in 2014-2016, to achieve positive year-on-year growth eight months in a row, although it comes on the back of a weak 2016.

Similar to Japan, following two years of negative industrial production growth rates, positive rates have returned in the US. Industrial production dropped as oil prices fell. However, as oil prices have now stabilised, growth has returned and industrial production now accounts for 19 per cent of the US GDP.

However, the GDP growth in other sectors of the US economy has not shown the expected strength and together with the expectation of fiscal policy being less expansionary than anticipated, the IMF and World Bank have both revised their expectation for US GDP growth in 2017, downwards.

USA

US labour market conditions continued to improve during 2017, and the unemployment rate for Q2 2017 fell to 4.36 per cent, the lowest level since Q1 2001. However, wage and productivity growth have remained sluggish, and hourly earnings have not increased, as had been the case in previous periods with low unemployment. There is optimism that the tightening of the labour market will trigger wage growth as weak productivity in 2016 may have constrained wages into 2017.

The downgrading of US GDP growth rates by -0.2 per cent for 2017 by the IMF, is the largest downward revision for a major economy in their recent update. It reflects the high possibility that the US will implement trade policies triggering retaliatory measures which could damage both the US and counterparties and reduce the possibility of tax cuts and investments in infrastructure to create stronger growth.

Europe

Despite optimism in the financial markets, stronger than anticipated domestic demand and reduced political uncertainty in the euro area, there is still a job to be done by policy makers and the European Central Bank (ECB) to avoid premature interest rate hikes, as seen in 2011.

The unemployment rate has continued to drop in 2016 and into 2017, reaching 9.2 per cent in the second quarter of 2017. This is the lowest level since Q1 2009, after the unemployment rate peaked at 12.1 per cent in 2013. However, the rate is still far above the structural level of unemployment, which signals that labour is still abundant in the Euro area. Moreover, capital goods could be used more productively.

Core inflation has risen in 2017 and is currently 1.3 per cent, but still below the ECB target of 2 per cent. However, while inflation is below the ECB target, it has accelerated to the highest level in four years.

The fact that the unemployment rate is falling and core inflation is increasing are encouraging signs for the Euro area and will be focal points when the ECB decides whether to extend the current quantitative easing programme or not, at its next meeting on 7 September 2017.

While the IMF has lifted its expectations for GDP growth in the euro area for 2017, by 0.2 to 2.1 per cent, it has downgraded its expectations for the United Kingdom by 0.3 to 1.7 per cent.

Asia

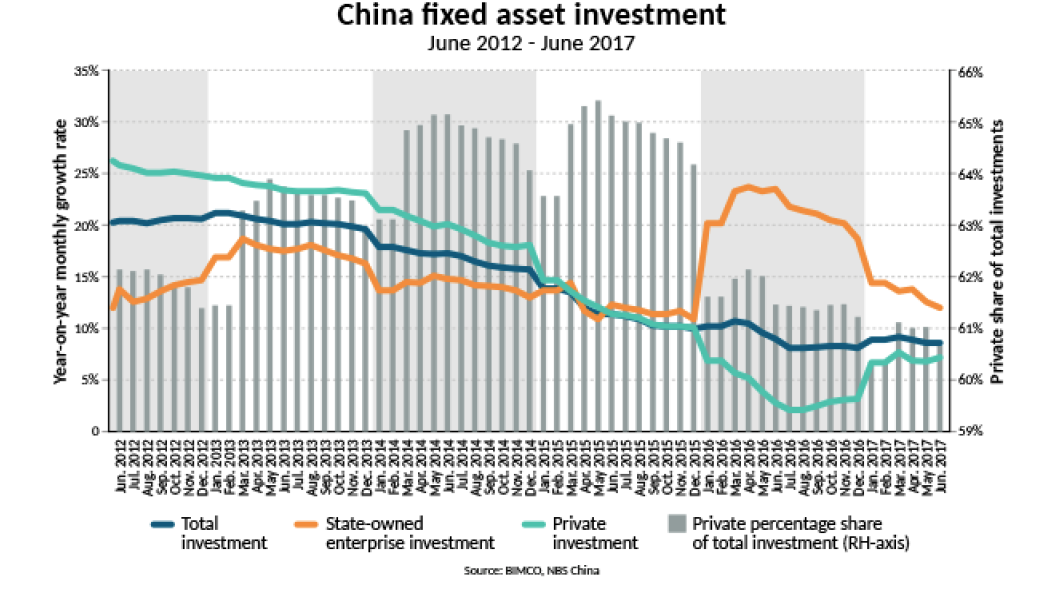

China’s GDP grew 6.9 per cent year-on-year in both Q1 and Q2 2017 and remains on track for its first annual growth acceleration since 2010. As a result, the IMF has upgraded its projections for China by 0.1 percentage point for 2017 and 0.2 percentage points for 2018. The stronger growth in GDP was driven by increasing growth in exports and a robust increase in consumption, despite limited state owned and private investment growth in fixed assets.

China has experienced year-on-year growth in fixed assets investments (FAI) stabilising at a level around 8.6 per cent in 2017. Despite a drop in private FAI for 2016, the growth rate for private investments has surged in 2017, and the FAI from state owned enterprises have also seen lower growth rates. Private investments are the main driver for FAI, as it represents 60 per cent of the total investments.

The notable shift in FAI from private and state-owned enterprises since January 2016 might be due to changes in the segregation of enterprise ownership. This raises the question whether the new segregation is the true picture of investments from private and state-owned enterprises (SOEs). The National Bureau of Statistics in China has not indicated the reason for the change.

Japan experienced GDP growth of four per cent in the second quarter of 2017. The growth of four per cent was not a one off, and was either caused by a surge in inventories, which will be worked down in the coming quarters or was a spike due to an imbalance between exports and imports. The GDP growth was primarily driven by strong domestic demand and consumption, while net exports were a slight drag.

This might indicate that the tight labour market is finally starting to lift consumer spending and will soon boost wages. Growing wages are a must to defeat low inflation.

The Japanese unemployment rate in Q2 2017 was 2.9 per cent, which is the lowest quarterly level together with Q1 2017 since Q2 1994. Impressively low, but also a result of a stagnating labour force, illustrated by weak Japanese wage growth.

Outlook

Despite global indicators for the four largest economies showing continued strength in the first half of 2017, global risk remains. Escalating trade restrictions could easily derail the fragile recovery in trade and it is vital that policymakers don’t underestimate the importance of nurturing the recovery and fostering long term growth.

With sustained low core inflation and soft upward pressure on wages, it is essential that expectations are consistently lifted in line with targets and output gaps using fiscal policies.

In the coming period, we might see the central banks in advanced economies gradually normalising their monetary policy, as inflation increases and labour abundancy diminishes. Similar to what is being seen in the US, where the tightening cycle is ahead of other major advanced economies.