EDITORIAL | The joke that is Indian “justice”: Piracy prevails

Long time readers of this website’s predecessor magazine Fishing Boat World may recall a series of articles in its August and September 2000 issues. They were titled: “Free passage” isn’t always free; The right of “free passage” should not be taken for granted; and, Indian Coast Guard won’t let go.

Basically, it involved what the English describe as a “nice little earner”. In this case it was a racket in which certain Indian Coast Guard officers arrested transiting Asian fishing boats returning home from African waters.

The vessel captains and, through them, their owners, were presented with the choice of paying a bribe of up to US$250,000 into a ready and waiting Swiss bank account.

Alternatively, they could waste years in the notoriously corrupt and inefficient Indian court system facing charges of illegal fishing in Indian waters. At the same time, their catch and fuel would be stolen by complicit local merchants in Kochi (Cochin) and their officers imprisoned.

Obviously, some fishing companies, particularly, I understand, some Taiwanese ones, chose to pay the bribe demanded because the coast guard officers had developed a sophisticated operation facilitated by their Swiss bankers. This was despite the fact that none of the examples I heard of had risked fishing in Indian waters.

Most were fitted with vessel tracking systems (VTS) that clearly showed they were sailing too fast to have been engaged in fishing. Further, all were passing southern India right on the Indian 200 mile EEZ line. They were clearly, as it turned out, the smarter owners. They paid the bribe and got on with life.

A “nice little earner”

Now, this kind of scam, it seems, is relatively common, particularly in various African countries and Venezuela. The Indonesian Navy and Coast Guard are notorious for it. Indeed, some young patrol boat captains are believed to have become quite wealthy from versions of it. I guess, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, their activities would have been described, quite favourably, as privateering.

The victim in this case was my friend of thirty years, Khun Wicharn Sirichai Ekawat, one of Thailand’s leading fishing operators. Khun Wicharn is an upstanding citizen, a former Thai Senator appointed to that role by the previous king. He is a significant philanthropist, particularly in the field of education. He is definitely not the kind of person to knowingly break the law or to risk his company’s hard-earned assets or reputation by doing so.

Is this a fishing net? Of course not!

Is this a fishing net? Of course not!

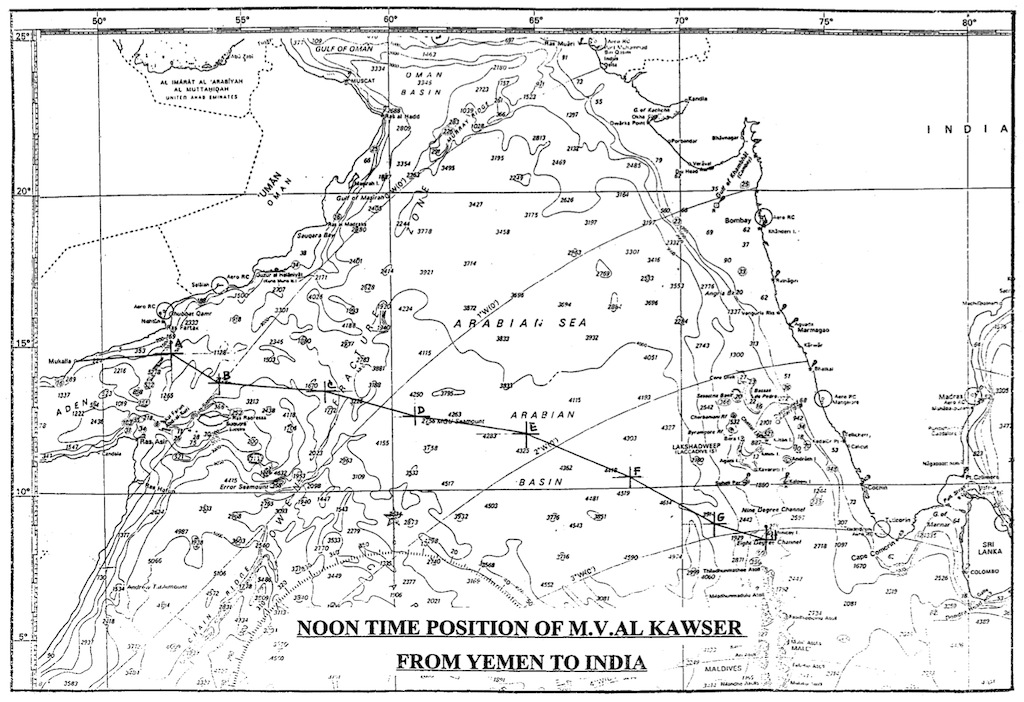

Briefly, the story was that the Sirichai Fisheries reefer vessel Al Kawser (note, not a fishing vessel!) was en route from Yemen to its base at Mahachai on the Gulf of Siam in Thailand.

It was loaded with 672 tons of cuttlefish, of a species not known to inhabit Indian waters. It was sailing at eight knots, much too fast to be conducting fishing operations or to tranship fish to or from another vessel.

Al Kawser carried no fishing gear whatsoever. She was on a steady course and, even to the most ignorant, was clearly not engaged in fishing. Her position was almost exactly 200 nautical miles from the south-west tip of India.

A cargo ship arrested for illegal fishing

That night, May 23, 2000, an Indian Coast Guard patrol boat captain decided to arrest Al Kawser on the very spurious grounds that she was fishing illegally in Indian waters. The ship was fired on, the crew arrested and the owners advised that their cargo would be sold at auction unless a bribe of US$80,000 was paid to “authorised officers”.

Well, Khun Wicharn, with many years of experience fishing in pirate infested waters, refused to take this threat lying down. He mobilised considerable diplomatic and legal firepower. Unfortunately, this effectively threw petrol on the fire.

The track of the Al Kawser

The track of the Al Kawser

The Indian Coast Guard was caught out and had to face the High Court of Kerala State. Sirichai Fisheries were forced to post a bank guarantee “bond” (better described as a ransom) of US$1 million to secure the release of its crew and vessel. Meanwhile, what remained of the catch after most of it had been purloined, had rotted, and most of the ship’s fuel was stolen.

The Indian Coast Guard found itself in an embarrassing situation that would only get worse. Its ridiculous response to my inquiry at the time is re-printed here:

India’s Coast Guard responds

Reprinted in full from Fishing Boat World, August 2000 edition, page 9:

Just prior to going to press, Baird Publications received a response to this article from SP Sharma, Commandant, Director (Operations), who comments:

“MV Al Kawser was sighted by a Coast Guard ship at about 21:45hrs on 23 May…doing a speed of 08 knots. The Coast Guard ship tried to establish communication with the vessel on VHF (MMB) channel 16, however, the later (sic) failed to respond despite repeated calls. On being challenged by the flashing light from Coast Guard ship signalling projector the vessel responded on VHF and revealed her identity as a Thai merchant vessel.

“The vessel on interrogation increased speed to 12 knots and started heading on a south easterly course towards the Indo Maldives Maritime Boundary Line. On repeated questioning on VHF the vessel responded with prevaricating answers such as transporting ‘cheap labour, newsprint and charcoal’ etc. On directions from Coast Guard ship to stop the vessel for interrogation, the master used abusive language and stopped only after warning shots were fired from the light machine gun across the bows. The vessel was finally boarded … at about 23:45hrs after two hours of hot pursuit.

“Following irregularities were observed on boarding the vessel: (a) vessel did not have a signed copy of the sale agreement onboard; (b) no valid document regarding change of name of the vessel were held; (c) no registration document including flag state details were held; and (d) no document supporting carrying of fish cargo on board such as bill of lading, export documents were held.

“Prima facie the vessel though not a fishing vessel violated MZI Act 1981 for transshipment of fish in the Indian EEZ without valid documents. The vessel was subsequently escorted to Kochi (Cochin) and handed over to Kochi Harbour police on 26 May 2000 for violation of relevant sections of the Maritime Zones of India Act 1981. A person so nominated by the court carries out the sale of fish through open auction under court directive.”

The letter then goes on to detail the Coast Guard’s role in patrolling the EEZ and in search and rescue, and summarises its performance record since 1978.

“In the past 22 years of its existence, the Indian Coast Guard has had an impeccable record of providing yeoman service t the Maritime Community and has received accolades from the world over. It is the unfortunate conduct of MV Al Kawser and its suspicious behaviour, which resulted in CG ship on patrol to board the vessel and investigate. Further investigation revealed the other side of the story as brought in preceding paragraphs.

“The ship was never called a ‘fishing vessel’ nor has it been charged for illegal fishing in Indian EEZ.”

Little knowing at the time how obscenely slowly the Indian “justice” system works, I editorialised then, as follows: “Needless to say, we will follow this story to its conclusion. Hopefully, by the time of our next issue it will have been successfully and happily resolved. I suspect not, however. There is now too much at stake”.

That conclusion took quite a while to be reached. I could never have imagined just how slow and unjust the Indian justice system could be, especially when it involved “privateering” Coast Guard officers and, presumably, their superiors. Nevertheless, I was still delighted when, more than eighteen years (and a series of court appeals) later, Khun Wicharn sent me a copy of the final judgement made in the High Court of Kerala on October 10, 2018.

“Justice” took more than eighteen years

Effectively, the judgement concluded that the prosecution was illegal. Further, it stated that no “authorised officer” existed. “The vessel and the proceeds of the fish seized from the vessel were not liable to be confiscated”.

Most importantly, it stated that, “The bank guarantee furnished by the petitioner (Sirichai Fisheries) shall be released to the counsel for the petitioner.

It might therefore be said that “all’s well that ends well”. Obviously, that does not apply in this case. Khun Wicharn and his company are still seriously out-of-pocket in this case.

They have also had further tragic difficulties with the Indians. In that case, with the Indian Navy, which very proudly and negligently killed 15 of his crew members and destroyed one of his boats off Yemen a few years ago.

The once impressive record of the Indian Coast Guard and Navy has been badly tarnished by these cases and others. Its judicial system is nothing short of a disgrace. Prime Minister Modi has much to do to restore the reputation of his country in all those areas.

Much as I hate to say this, there are some countries where, if you find yourself in a situation like Khun Wicharn’s, it may be better to just pay the bribe and get on with your life. I congratulate Khun Wicharn on his persistence, forbearance and honesty in this case.