COLUMN | The dragon rises: Siemens Gamesa; Iberdrola; Japanese and Chinese floating wind; a solar panel warning [Offshore Accounts]

Two weeks ago (here) we reported on the profit warnings in offshore wind from industry leaders Equinor and Ørsted. Equinor reported that fierce bidding from BP and others was driving up the costs of acquiring sites for wind farms and would depress future returns, whilst Ørsted announced that it faced a US$489 million charge for the cost of remedial repairs on damaged subsea transmission cables and scour protection at its offshore turbines in ten North Sea locations.

This is an industry that is in a frenzy of investment, but the leading players seem less certain that they will actually make decent returns. Equinor is now forecasting just a four per cent return from its renewables division compared to 30 per cent for its new oil and gas projects. In fact, some players are even losing money, even as wind farm installations worldwide surge, in line with Clarkson-Platou’s famous “hockey stick graph” (here).

How is it possible not to profit in a once in a lifetime gold rush?

Siemens Gamesa: cost pressures destroy margins

The problem is that costs for turbine manufacturers are rising faster than prices can be increased for end customers. Just ask Siemens Gamesa. Last week shares in the world’s largest manufacturer of offshore wind turbines collapsed 18 per cent after the company issued its second profit warning in just three months (Reuters coverage here). In the best case now, the Spanish maker of turbines forecasts it will break even this year. Worst case, it will lose money.

Siemens Gamesa’s problems lay onshore in Brazil, where the doubling of steel prices and bottlenecks in the supply chain have led to the company making a loss on its 5X design turbines. Any offshore company could have warned Siemens Gamesa that Brazil is a high-cost market famed for some extraordinary costs given that it is a relatively poor country. Unfortunately, the formal sector of the Brazilian economy is burdened with high customs duties, high taxes, many pension charges and various levies, even as household income per head is less than US$5,000 (here).

Now, Siemens Gamesa told markets it expects its 2021 revenue to be at the low end of a previously guided range of US$12 billion to US$12.4 billion.

Vestas falls too

Unfortunately, the rise in raw materials will also hit the company’s offshore projects as well, and is general to the turbine manufacturing industry. As a result, Danish competitor Vestas, which is the world’s third largest maker of wind turbines, fell 6.5 per cent too. Fortunately, the Financial Times reported (here) that steel only “represents between 10 and 15 per cent of turbine input costs. Price rises are more than offset by increases in wholesale power prices. Two-year forward prices have surged 20 per cent this year in Germany, pushed higher by rising carbon and gas expenses.”

Is this the start of a general inflation problem?

So, whilst turbine makers are squeezed today, the end user utilities expect to have higher prices for customers, just as the take-off of electric vehicles causes demand for electricity to surge in North America and Western Europe. If much higher prices for electricity are being baked into futures markets, this may signal that the Federal Reserve’s hopes that the current rise in inflation is “transitory” are misplaced. This has significant consequences for the entire economy, and for ship owners looking to fix vessels on long-term contracts if prices and wages rise more generally over the next few years.

Given the rising costs of offshore wind farm acreage in government leases, the utilities and energy companies building offshore wind farms will need all the wholesale price increases they can get. Last week Shell announced it was partnering with Iberdrola’s Scottish Power unit to tender to the Scottish Crown Estate for a floating offshore wind farm in the Scotwind licencing round (which we covered earlier here). BP, Equinor and Germany’s RWE have also declared that they have placed bids. The round is likely to be one of the most expensive for bidders in history.

Iberdrola does it again, Repsol and ENI too

One company with form in making money from renewables is Iberdola; not necessarily from making profit in generating electricity from solar and wind and hydro, but from flipping subsidiaries to external investors. In December 2007 Iberdrola spun off its renewables division, Iberdrola Renovables, in an initial public offering on the Madrid Stock Exchange, selling 844,812,980 new shares at a price of €5.30 (US$6.24) each. The €5 billion (US$5.89 billion) floatation was the largest placement ever made on the Spanish market by a new company. But then, after the global financial crisis, the shares fell, and in July 2011, Iberdrola took Iberdrola Renovables back again in an all-share merger, which valued each share of Iberdrola Renovables at around €3 (US$3.53).

Ouch.

It’s happening all over again

Now Iberdrola says it is looking at spinning off its renewables assets a second time. The Financial Times reported (here) that Goldman Sachs estimated Iberdrola’s renewables business is worth between €15 billion and €20 billion (between US$18 billion and US$24 billion). The division contributed €600m (US$720 million) of Iberdrola’s earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation last year, Iberdrola’s CEO said, commenting that the business had “hidden value.”

This can only encourage high bidding by Iberdrola in the Scotwind acreage round as the new company will need to demonstrate a pipeline of new projects in offshore wind, just as BP and Shell also need to show progress in their transformations into low-carbon energy producers.

Repsol and ENI are also reported to be considering spinning off their renewables businesses as well. This offshore wind gold rush has a lot longer to run, and governments stand to benefit, even as consumers face higher prices, and industry players face squeezed margins.

Floating wind, the next frontier?

Iberdrola and Shell’s focus on floating wind in Scotland may offer light at the end of the tunnel for beleaguered North Sea anchor handler owners like Maersk Supply Services, United Offshore Support and Solstad, albeit only in the longer term. Whilst summer rates for rig moves have spiked as high as £45,000 (US$63,000) in the last month, utilisation has remained sluggish since the downturn began in 2015. Fast tracking offshore floating wind with its requirement for multiple heavy moorings to be installed by AHTS would be a much-needed boost for anchor handler demand by the end of the decade.

Today, Europe hosts only two floating offshore wind farms, as per WindEurope (here). These are Equinor’s 30MW Hywind Scotland project in the UK, where the 100-metre-high turbines were installed on their floating foundations by Saipem’s heavy lift vessel Saipem 7000 (here), and the 24MW Windfloat Atlantic project in Portugal, which was installed by Bourbon Subsea Services in 2020, with the pre-assembled turbine and foundation towed offshore by Bourbon Orca and tugs (here).

Additionally, BW Ideol has deployed its floating foundations as part of the Floatgen project off Le Croisic, France, on the Brittany coast. This involves a 2MW Vestas V80 turbine mounted on the floating BW Ideol Damping Pool foundation. The test unit commenced electricity generation for the French national grid in September 2018 (see our coverage here).

BW Offshore targets growth through BW Ideol

As we reported in February (here), FPSO operator BW Offshore has purchased floating wind turbine foundation designer Ideol of France and taken the company public. A private placement of new shares for BW Ideol was completed ahead of the new company’s listing on the Oslo Stock Exchange in March. This raised NOK575 million (US$65 million) in gross proceeds to fund the company’s research and development and working capital for growth. This potentially sets up the BW-controlled company as a serious player in the floating wind sector.

WindEurope reports that seven European countries intend to install floating offshore wind commercially in the next decade (France, UK, Portugal, Italy, Spain, Norway, Sweden) with Ireland, Greece, Bulgaria, and Romania also considering the concept as well. The industry body has forecast as much as seven GW of total installed floating wind capacity in Europe by 2030.

The future is rosy for floating wind, but progress will take time.

Japan’s tentative steps

But for how long will Europe maintain its lead in the floating wind business?

Japan is tentatively progressing with floating wind trials, which must be good news for Fukada Salvage, the main offshore vessel operator in the country.

Japan trialled three different-sized floating turbines off Fukushima, the site of the catastrophic nuclear reactor failure in 2011. However, due to low utilisation, the 7MW Hitachi test turbine was removed last year, whilst the remaining 5MW and 2MW Hitachi test turbines will be decommissioned and removed this year, according to the industry press (here).

In 2019, a second test facility was launched by New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO) off Fukuoka. The Hibiki turbine barge features the Aerodyn SCD 3MW two-bladed turbine installed on Ideol’s Damping Pool floating foundation. The demonstrator is located off Kitakyushu Port, and was taken offshore in August 2018. It weathered three super-typhoons just after the installation, according to BW Ideol (here).

Japan goes carbon-neutral

The omens look good in Japan for floating wind, even if the Fukushima test was a flop: in 2020 Japanese prime minister Yoshihide Suga declared the country’s commitment to reach carbon neutrality by 2050, and Japanese industry bodies expect that Japan will need around 90 GW of offshore wind capacity, both floating and fixed. In June this year, Hitachi-ABB announced it would bee co-operating with BW Ideol on floating substations to provide a modular solution for deep waters to replace the jacket-mounted substations used for fixed-foundation turbine fields. The press release is here.

Last year Suga’s government launched Japan’s second offshore wind acreage auction, offering four monopile fixed foundation wind farm sites off Akita and Chiba. These have not yet been awarded.

A separate tender for a floating offshore wind project off Nagasaki was awarded to the sole bidder, a consortium of six companies headed by Toda Corporation, this June (here). But at only 16.7MW capacity, this is also barely more than a trial. However, it is a trial which will use BW Ideol’s patented Damping Pool® technology for the floating foundations, the company said (press release here).

China enters floating wind

Depending on how you look at it, China has already revolutionised the solar panel industry, and the shipbuilding industry. Alternatively, you might feel that it has come to dominate the solar power and shipbuilding industries by dumping prices, using state subsidies, erecting barriers to entry to its home market, and harnessing highly polluting but very cheap coal energy to crush its foreign opponents.

If you are going to burn four billion tonnes of coal a year (as we reported here), producing half the world’s steel and the largest amount of CO2 of any nation globally, then you should have some strategic advantage for all the pollution you produce, right?

Bloomberg reported on “How China Beat the US to Become World’s Undisputed Solar Champion” in June (here). This documents how “China went all in on solar manufacturing and now produces three-quarters of the world’s supply.”

The report highlights that twenty years ago American factories made 22 per cent of global solar panels, but they now produce just 1 per cent on American soil, according to Jenny Chase, head of solar analysis at BloombergNEF. China produces 75 per cent of world supply.

Will China do the same in wind power?

Lower costs: how and by whom?

The future of offshore wind depends on driving down the cost of installation and increasing the quantity of electricity generated from each unit. This requires bigger turbines and cheaper floating foundations. Standardised production in large fabrication facilities, cheap steel, and low labour costs will help drive down overall costs.

We have already seen that Chinese domestic companies are building wind farm installation vessels for monopile turbine installations – vessels that are 40 per cent cheaper than the Danish-owned units ordered by Cadeler and Eneti recently (here).

Wison and Ming Yang Smart Energy install the first…of many?

Now China has entered floating wind. Western European companies in the space, like BW Ideol and SBM, should be anxious.

Last month, Chinese offshore yard Wison Offshore and Marine announced it has delivered the country’s first floating wind turbine unit for an offshore wind farm developed by China Three Gorges, a major state-owned electricity producer. The company was on a list of Chinese state-owned companies with affiliation to the People’s Liberation Army subject to sanctions prepared by the Trump administration in 2020 (here).

The floating wind turbine unit was towed out last month from Wison’s Zhoushan facility in Zhejiang province for deployment in the South China Sea off Guangdong. The floating base measures 91 metres by 32 metres, and China Three Gorges claims it is typhoon-proof, like the smaller Hibiki unit in Japan. The floating turbine has 5.5 MW of capacity and a blade diameter of 158 metres.

Chinese manufacturers are scaling fast.

Seven out of ten ain’t bad

If Siemens Gamesa thinks it has problems in Brazil today and can’t make money selling its turbines now, competition is only going to heat up. China destroyed the western solar manufacturing industry in less than a decade. It can easily do the same in wind turbines over the coming decade using the same advantages – state subsidies, cheap coal-powered energy, and cheap steel as inputs, and a lower cost of labour compared to rival manufacturing facilities in Europe or North America.

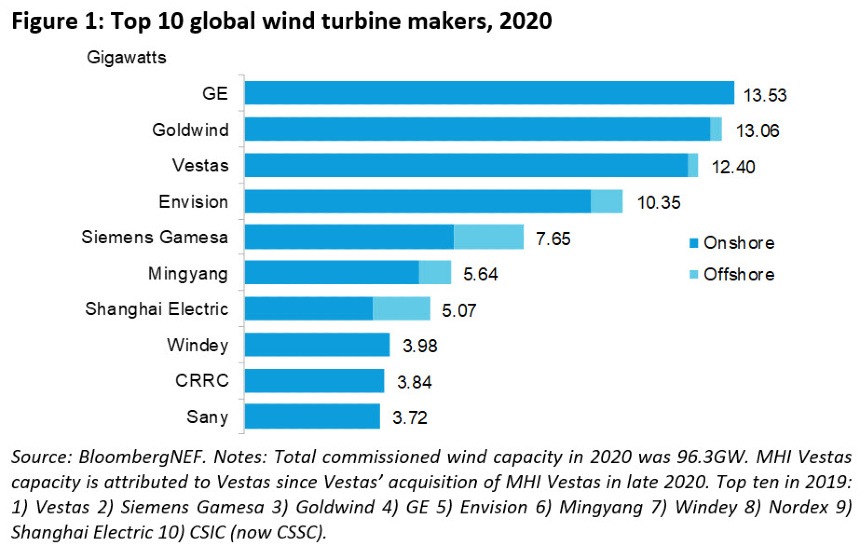

The Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF) ranking of global wind turbine manufacturers for the year 2020 showed that seven of the top ten wind turbine manufacturers are now Chinese companies.

General Electric of the US tops the table, with Goldwind of China in second place. Vestas fell from the top position in 2020 for the first time in five years, and ended up in third place (here). Siemens Gamesa is ranked leader for offshore turbine capacity installed globally in 2020, but Shanghai Electric and Ming Yang both recorded significant growth to take second and third place.

China is now a wind power

BNEF reported that more than half of the world’s newly installed wind power capacity was installed in China in 2020, almost equal to the entire global growth in wind farm capacity in 2019.

China’s neighbours Japan, Korea, Vietnam and Taiwan are caught in a strategic bind and likely will avoid using Chinese installation companies and vessels, but other countries in Asia and further away will probably find lower-cost Chinese fabrication and installation contractors and lower-priced Chinese turbines as compelling.

The western European and American manufacturers are going to have to get very political to ensure that jobs and technology in wind stay at home. Otherwise, wind turbines both fixed and floating can go the way of solar panels, an industry which Chinese companies completely dominate globally with a completely integrated domestic supply chain. If China can match Western floating wind projects now, there is only a limited technical edge left to the incumbents internationally. They may have to resort to protectionism and local content laws, like Norway already does in oil and gas.

The western oil majors entering the wind business are paying ever higher prices for wind acreage; for them, too, Chinese equipment will be attractive as a cost-saving measure – many of them already use Chinese shipyards for their FPSOs, jackets and platforms in their offshore fossil fuel divisions.

A warning

GE, Vestas and Siemens Gamesa need to play their cards right to prevent them becoming casualties of yet another Chinese trade success. Bloomberg quotes Sarah Ladislaw, a senior adviser at the Center for Strategic and International Studies on how China won the battle over solar panels.

“They tried harder than us,” Ladislaw said. “China had a plan and they executed to the plan. They had policies to create supply, they had policies to create demand, and they executed on it.”

You have been warned.