FEATURE | ATSB releases findings on Saxon Onward/Beijing Bridge collision

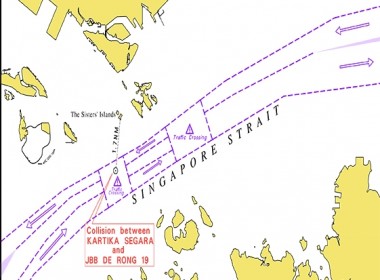

On January 23 this year, at about 00:15 Eastern Daylight-saving Time, the fishing vessel Saxon Onward collided with the container ship Beijing Bridge about three nautical miles south-east of Gabo Island, Victoria. Saxon Onward was bound for Eden, New South Wales while Beijing Bridge was en route to Melbourne, Victoria from Taiwan.

At about 20:30 on the evening of January 22, the 294-metre container ship Beijing Bridge was about 29nm off the southern coast of New South Wales bound for Melbourne with arrival expected late the next evening. The ship’s master had retired to his cabin for the night and the third officer was the officer of the watch (OOW) and sole lookout on the navigational bridge (bridge).

The ship was on autopilot maintaining a heading of about 206º with a speed of about 17 knots. The night was clear with good visibility and the seas calm, with a south-westerly wind at about five to ten knots and little swell.

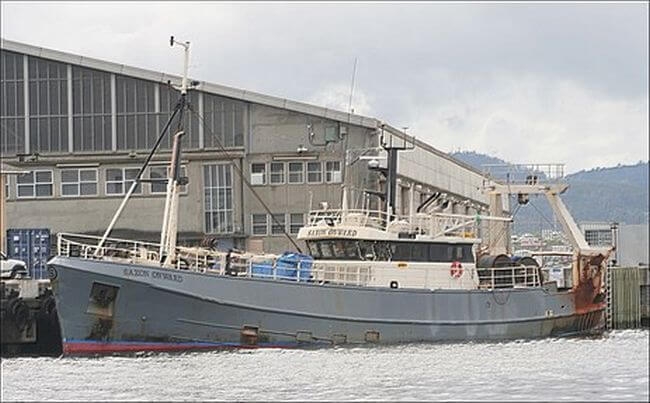

Meanwhile, Saxon Onward, a 32-metre trawler, was northbound for the port of Eden to discharge its catch having completed a few days fishing off the coast of Tasmania. The trawler was on autopilot maintaining a heading of about 038º with a speed of about 8.5 knots.

At about 22:00, the skipper handed over the watch to the 22:00-24:00 watchkeeper. The fishing vessel Rubicon, also bound for Eden, was on a parallel course about three nm away on the starboard bow, slowly being overtaken by Saxon Onward.

Sometime between 23:20 and 23:30, Saxon Onward’s watchkeeper sighted the masthead lights and green sidelight of an approaching ship (Beijing Bridge) on the starboard bow. The ship was also detected on radar but was not acquired for tracking at that time.

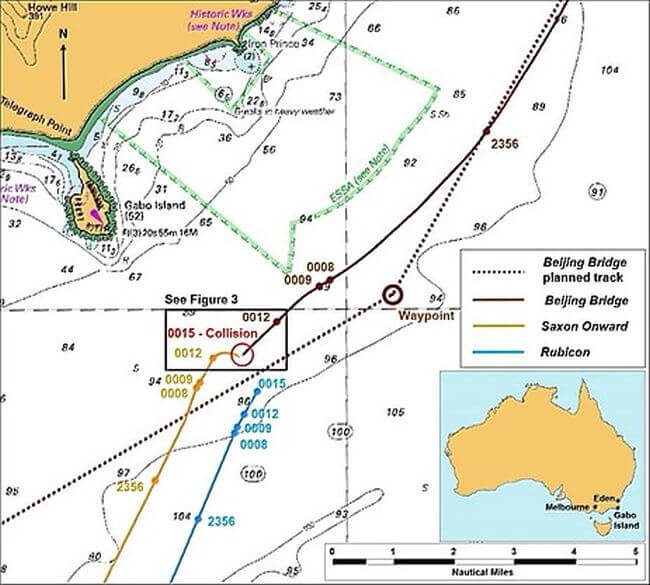

Shortly after, at about 23:35, with the ship on a heading of 209º, Beijing Bridge’s OOW sighted the two approaching vessels (Saxon Onward and Rubicon) on the starboard bow. The two vessels were also detected and subsequently acquired on the ship’s radar by the OOW. By about 23:52, the two fishing vessels were about 10nm from Beijing Bridge. The OOW continued to monitor the two vessels, both visually and by radar, while making small adjustments to the heading to maintain the ship on the planned track.

At about 23:56, with Beijing Bridge now on a heading of 216º, the OOW commenced a course alteration to starboard about 3.2nm in advance of a planned course alteration position (waypoint). Over the next 10 minutes, the OOW made a succession of small heading alterations that took the ship further to starboard, away from the planned track.

Meanwhile, at about midnight, Saxon Onward’s 24:00-02:00 watchkeeper made his way to the vessel’s wheelhouse to take over the watch. The previous watchkeeper stayed on for a few minutes to handover before retiring to his cabin.

After taking over the watch, the 24:00-02:00 watchkeeper immediately acquired Beijing Bridge on the radar and noted that the approaching ship on the starboard bow was about 6.5nm away on a south-westerly course with a speed of about 17.5 knots. He also noted that Rubicon was now about 1.5 to 2.0nm away on the starboard beam.

At about 00:05 on January 23, with Beijing Bridge about 4nm away, Saxon Onward’s watchkeeper left the wheelhouse and walked the short distance to the trawler’s bow to better assess the situation. He sighted Beijing Bridge fine on the starboard bow with the ship’s two masthead lights (nearly in a line), green sidelight and deck lights visible. He then returned to the wheelhouse and continued to monitor the approaching ship visually and by radar while maintaining Saxon Onward’s course and speed.

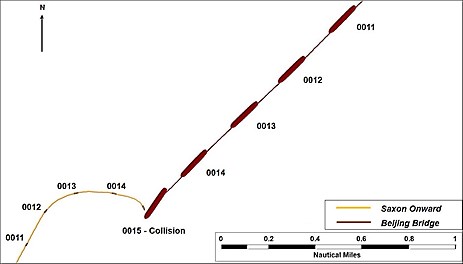

By about 00:08, Beijing Bridge was steady on the new course with a heading of 241º and was about 0.75nm to starboard of the ship’s planned track with Saxon Onward fine on the ship’s port bow. About a minute later, the OOW altered the ship’s heading to port with the intention of passing between the two trawlers and increasing the distance at which Saxon Onward’s closest point of approach (CPA) would occur. The ship eventually settled on a heading of 228º at about 00:12 with Saxon Onward, now on the ship’s starboard bow.

Shortly after, Saxon Onward’s watchkeeper commenced a rapid turn to starboard at a distance of about one nautical mile from Beijing Bridge.

In response, Beijing Bridge’s OOW altered the ship’s heading to port from 228º to 225º and flashed the ship’s Aldis lamp at Saxon Onward followed by a long blast on the ship’s whistle. Woken by the whistle, the ship’s master called the OOW on the bridge telephone to find out what was happening and was told that he was needed on the bridge. The OOW then continued to sound long blasts on the ship’s whistle. At about 0014, the OOW changed the steering over from autopilot to hand steering and placed the wheel hard to port.

A few seconds later, the master arrived on the ship’s bridge and saw the lights of the trawler, on the starboard side, rapidly closing on the ship. He also immediately ordered “hand steering” and “hard to port”, and confirmed that the ship was beginning to turn to port. The master ordered the OOW to continue blowing the whistle and then went out on to the starboard bridge wing.

Meanwhile, on Saxon Onward, the watchkeeper realised that the trawler was in danger and shouted to alert the skipper and crew. At about 00:15, as the skipper arrived in the wheelhouse, Saxon Onward collided with Beijing Bridge.

The trawler’s port bow impacted the ship’s starboard side in the region of cargo hold number 3, about 94 metres aft of the ship’s bow. As the trawler then scraped down the ship’s side, the skipper stopped the engine and the crew mustered in the wheelhouse. The trawler heeled over sharply to starboard and took on some water before it righted itself, passed the ship’s stern and drifted away to the north-east.

Beijing Bridge continued turning to port with a corresponding reduction in speed. The master then ordered “hard to starboard” and shortly after, “stop engine”. At about 00:17, the master called Saxon Onward on the radio and requested a damage report. At about the same time, Rubicon passed clear to port of Beijing Bridge at a distance of about 0.5nm and continued its passage to Eden.

In the following minutes, as Saxon Onward’s crew inspected the trawler for damage, the skipper advised Beijing Bridge of the trawler’s name and that they did not require assistance. Beijing Bridge’s master then made contact with their company superintendent and designated person ashore to brief them on the situation and obtain advice. He also ordered a damage assessment of the ship and initiated the save procedure for the ship’s voyage data recorder (VDR).

At about 00:35, after seeking advice from the company superintendent and designated person ashore, Beijing Bridge’s master made two attempts to contact Saxon Onward on the radio with no response received. Shortly after, Beijing Bridge’s main engine was restarted and the ship’s heading was gradually altered to resume its original course. At about 00:39, analysis of VDR data from Beijing Bridge shows that Saxon Onward turned around and began slowly to make its way back towards Beijing Bridge.

A few minutes later, the trawler’s skipper broadcast a call on the radio with no response received. As Beijing Bridge resumed its south-westerly course, Saxon Onward increased speed in an attempt to catch-up with Beijing Bridge. However, at about 0047, with Beijing Bridge steadily increasing speed and moving away, Saxon Onward also turned back onto a north-easterly course and resumed its passage to Eden.

Beijing Bridge berthed at Melbourne later that night and was attended by Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) surveyors the next day (January 24). The ship sustained minor damage, including indentations to the hull and scratch marks down most of the ship’s starboard side. Beijing Bridge was detained while the authorities conducted inspections and collected evidence before being released to continue its voyage on January 25.

Saxon Onward arrived safely in Eden at about 0600, six hours after the collision and was attended by AMSA later that afternoon. The trawler sustained substantial damage to the port bow, structural cracks and displacement of the port side A-frame arm and structural damage to deck fittings. The trawler also lost a net overboard and sustained seawater damage to an auxiliary engine, a generator and to cabin fittings.

Beijing Bridge

Beijing Bridge’s master joined the ship in November 2017 and held a Bulgarian master’s certificate of competency with at least 14 years’ experience in the rank of master. The third officer joined the ship in July 2017 and held a Philippines watchkeeping deck officer’s certificate of competency with at least eight years’ experience as an OOW.

The ship was fitted with the required navigational equipment including electronic chart display and information systems, radar with automatic radar plotting aid capability, automatic identification system (AIS), VDR and radio equipment as required by SOLAS.

Lookout

International regulations and Beijing Bridge’s company procedures both specified that the OOW could be the sole lookout on the bridge only during daylight hours. However, there was no lookout posted on the bridge during the 20:00-24:00 watch, at the time of the collision and for several weeks preceding. The ship’s master had the 20:00-24:00 lookout re-assigned to day work duties in an effort to direct more manpower towards maintenance and repair activities.

Repairs of the ship had been ongoing since it had re-entered service in July 2017 after being laid-up for 18 months. Safety and maintenance related deficiencies had been identified by an AMSA inspection during the ship’s port call at Melbourne in September 2017 resulting in the ship being detained and issued with two prohibition notices. AMSA inspections during subsequent port calls at Melbourne in November and December also resulted in the issuance of prohibition, improvement or direction notices to the ship.

Following the collision, AMSA detained the vessel in Melbourne based on several identified deficiencies such as the lack of a bridge lookout on the 20:00-24:00 watch. The nature of the identified deficiencies indicated that the ship’s safety management system (SMS) as implemented, did not ensure compliance with procedures for critical shipboard operations such as navigational watchkeeping. The AMSA report of inspection also noted that the ship’s last internal audit in September 2017 identified similar SMS related deficiencies indicating ineffective internal audit processes.

Collision avoidance

Beijing Bridge’s company procedures and master’s standing orders required early and effective action be taken to avoid collision, in accordance with the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, 1972, as amended, (COLREGs). The procedures and standing orders specified that course alterations were to be clear and made in sufficient time so as to leave no doubt as to the ship’s intentions.

The procedures and standing orders also required the action to result in the ship keeping a minimum CPA of at least one nautical mile from other vessels. If the OOW’s action did not have the desired effect and the minimum CPA could not be maintained, the master was to be called.

Saxon Onward

Saxon Onward’s skipper held a skipper’s certificate of competency with about 33 years’ experience in the fishing industry. The 24:00-02:00 watchkeeper had recently obtained his deck watchkeeper’s certificate of competency and had about four years’ experience in the fishing industry.

The trawler was equipped with the required navigational equipment for a vessel of its class including radar with automatic radar plotting aid capability, chart plotter, echo sounder and radio equipment. The trawler was not equipped with, nor was it required to be equipped with AIS or VDR.

Collision regulations

COLREGs provide internationally agreed rules to prevent collisions and generally apply to all vessels at sea. The COLREGs lay out requirements for every vessel to maintain a lookout, to take action to avoid collision in accordance with the rules and to exhibit specific lights (navigation lights) from sunset to sunrise.

Beijing Bridge and Saxon Onward both exhibited the navigation lights required by the COLREGs for power-driven vessels of their size. In addition, both vessels also had some of their deck lights on.

The COLREGs also provide rules detailing the actions required of vessels in specific situations involving risk of collision such as head-on situations, crossing situations and overtaking situations. Rule-14 requires vessels meeting in a head-on situation involving risk of collision to each alter their course to starboard. The rule also makes it clear that in the event a vessel is in any doubt as to whether a head-on situation exists, they are to assume that it does and act accordingly.

The rules also state that any action to avoid collision should, among other things, be positive, be large enough to be apparent to an observing vessel (while avoiding a succession of small course and/or speed alterations) and be made in ample time. More specifically, the rules require that any alteration of course to avoid a close quarters situation should be made in good time, be substantial and not result in another close-quarters situation.

Finally, Rule-2 of the COLREGs allows that in special circumstances, it may be necessary for vessels to deviate from these rules in order to avoid immediate danger.

Safety analysis

While Beijing Bridge was on its planned track, the traffic situation was relatively benign with neither Saxon Onward nor Rubicon posing a risk of collision. Beijing Bridge’s officer of the watch (OOW) then commenced a course alteration to starboard more than three nautical miles in advance of the planned waypoint in the vicinity of Gabo Island, Victoria.

The OOW, believing it was safe to do so, commenced the course alteration early to effect a “short-cut” and indicated that it was common practice for him to do so. While it is not unusual for ships to make minor departures from the passage plan, in this instance, the decision to alter course in advance of the planned waypoint resulted in a close quarters situation with risk of collision developing with Saxon Onward.

Beijing Bridge’s company procedures and master’s standing orders required early and effective action be taken to avoid collision in accordance with the COLREGs. They also specified that course alterations were to leave no doubt as to the ship’s intentions. Shortly before the collision, at a range of about three nautical miles from Saxon Onward, Beijing Bridge’s OOW carried out a 13° course alteration to port in an attempt to increase the distance at which Saxon Onward’s closest point of approach (CPA) would occur.

This action was based on the OOW’s assumption that Saxon Onward would cross the ship’s bow from port to starboard and pass clear down the ship’s starboard side. However, this action failed to resolve the close quarters situation and would have resulted in a CPA that was less than the minimum distance required by the procedures. The action also increased the risk of a collision in the event Saxon Onward decided to take action in accordance with the COLREGs, as subsequently occurred.

Further action, taken in response to Saxon Onward’s course alteration to starboard, including the final turn to port, was not effective in avoiding the collision either. Furthermore, the master was not called during the developing situation and was only alerted to the impending collision by the ship’s whistle. Consequently, he arrived on the bridge too late to affect the outcome of the situation.

Saxon Onward’s 24:00-02:00 watchkeeper had acquired Beijing Bridge on radar and then continued to monitor the situation, including Beijing Bridge’s succession of course alterations, both visually and by radar. The watchkeeper then assessed the trawler and the ship to be in a head on situation with risk of collision.

In response, and in accordance with the COLREGs, the watchkeeper then initiated a bold alteration of course to starboard. However, this action, taken at the relatively close range of about one nautical mile, was too late to have a positive effect on the situation and resulted in the collision.

On board Beijing Bridge, the re-assignment of the bridge lookout to day work duties left the OOW as the sole lookout on the bridge during the hours of darkness of the 20:00-24:00 watch on the night of the collision and for several weeks preceding. This was in contravention of the company’s procedures and international regulations. While in this case, the absence of the bridge lookout did not affect the OOW’s ability to detect Saxon Onward, it increased the risk of vessels going undetected over a period of several weeks prior to the collision.

Findings

According to the ATSB, Beijing Bridge’s planned alteration of course, to starboard, executed in advance of the passage plan waypoint, placed the ship in a developing close quarters situation involving risk of collision with Saxon Onward.

Beijing Bridge’s subsequent alteration of course was neither substantial nor made in good time and was inconsistent with the master’s standing orders, company procedures and the COLREGs. The action failed to remove the ship from the existing close quarters situation and increased the risk of a collision.

Saxon Onward’s alteration of course to starboard was made in response to the head-on situation that the watchkeeper assessed the vessel to be in. The alteration, while substantial, was not made in sufficient time to have a positive effect on the situation and resulted in the collision.

Beijing Bridge’s officer of the watch was the sole lookout on the bridge during the 20:00‑24:00 watch on the night of the collision and for several weeks preceding the collision. The absence of the bridge lookout during hours of darkness increased risk and was in contravention of company procedures and international regulations.

Safety action

As a result of the incident, Beijing Bridge’s management company, V.Ships of Germany, has advised the ATSB that it has issued a circular requiring all managed ships to hold a safety meeting at the earliest opportunity to discuss the collision and its lessons.

The circular required the ship’s masters and bridge watchkeeping personnel to review compliance with the COLREGs and the ship’s SMS with particular emphasis on statutory requirement to have a lookout on the bridge during hours of darkness and restricted visibility; calling the master in good time; safe speed and the use of main engines to avoid collision; and areas of likely concentrations of fishing vessels to be taken into consideration during passage planning.

The company also mandated that passage plan tracks were to be laid at least 10nm from the shoreline where possible.

Saxon Onward’s master has implemented a policy of maintaining two watchkeepers on duty in the wheelhouse when transiting through high traffic density areas. The vessel has installed AIS equipment and has since reported an improvement in traffic awareness.

Safety message

The ATSB said at least 65 collisions between small vessels and trading ships on the Australian coast have been reported (with 39 investigated) since 1990. Safety investigations into several of these collisions showed that taking early and effective avoiding action and the keeping of a proper lookout in accordance with the COLREGs could have prevented most of these collisions.

ATSB said planned course alterations at waypoints should be risk assessed taking into account the traffic situation and movement of vessels in the vicinity. Course alterations at waypoints should also be conducted so as to minimise the risk of the alteration generating close quarters situations or risk of collision. While an alteration of course, for whatever purpose, may be logical to an officer on their own ship, the action may be confusing and open to interpretation by observing vessels.

The safety of fishermen and people in small boats continues to be a concern in terms of safety at sea. When fishing in waters off the Australian coast, fishing vessels regularly encounter large trading ships carrying a variety of cargoes to and from Australian ports. When these vessels collide, a fishing vessel, being smaller than a ship, will almost always come off worse after a collision, often with potentially serious consequences to the lives of those onboard.